We Aren't Materialists. We're Introverts.

On loneliness, longing, and Rom-Coms in 2025.

Hello friends,

Two small housekeeping items:

I’ve decided to start including a brief list of things I’m reading/watching at the bottom of each newsletter. It’s not related to the topic at hand. It’s just another way to share some interesting stuff, and I’m always curious to hear your thoughts if you’re reading/watching it too.

This essay references two movies from the last few years, Materialists and Past Lives. I promise it will make sense even if you have not seen either of them, so please don’t be discouraged.

As a final note, this essay was by far the most frustrating and difficult to write yet. Like, weirdly hard. I am still not fully satisfied with the ideas I’m conveying nor the way I’m conveying them. But I hope it’s enough to provoke at least some self-reflection and general pondering for you. In that vein, please never hesitate to leave a comment, give it a like, or (most importantly) share it with someone new :)

Be well,

Ollie

The year is 2023. It’s a Tuesday night and I’m sitting alone in my empty studio apartment, sprawled out on my leather loveseat that fits one person much better than two.

My phone lights up. A text from my sister in a groupchat with my Mom. They’ve just seen what will go on to be a sleeper favorite for the Year In Film: Past Lives. I have to watch it, they say. Just wait til the end. You’ll love it.

So with nothing better to do, I shelled out the $3.99 to rent it and watched. One hour and forty-six minutes later, I send another text in the same groupchat:

“Guys, why did you just make me cry on a Tuesday?”

Past Lives was a masterpiece. Precisely written, beautifully shot, and brought to life by a perfect cast, it tells the story of two childhood Korean friends separated by one’s immigration to the United States, who then grow up in two completely different directions. Two decades later, they reconnect, and confront the love they felt as kids in the bodies and circumstances of two very different adults (one of them happily married). It’s steeped in a melancholic longing that resonates with anyone who has known the one-that-got-away, all culminating in a type of happy ending you didn’t know could be happy.

So you can imagine my masochistic excitement when I heard that the writer/director of Past Lives, Celine Song, came out with a new film this year: Materialists.

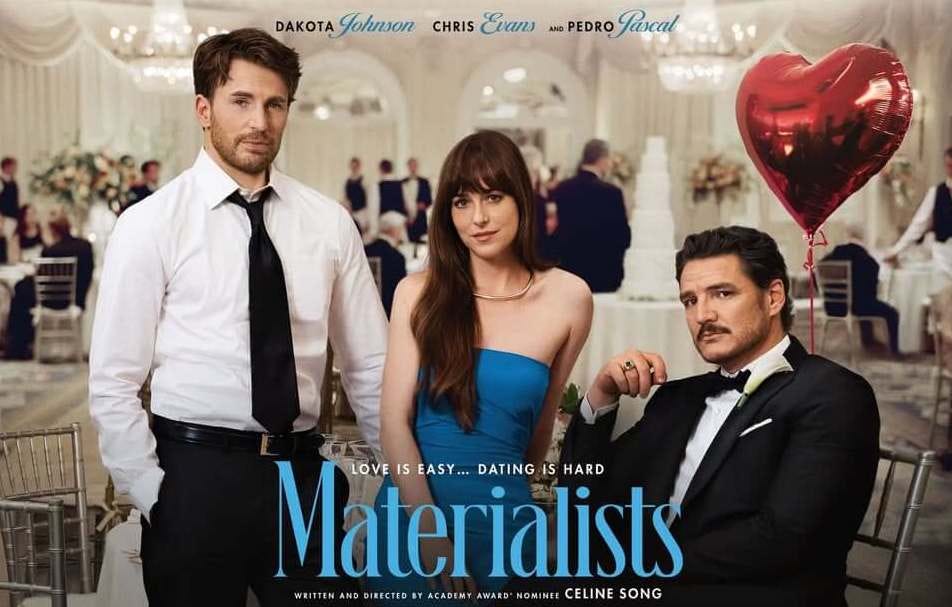

Materialists was also about love, but a very different kind. Starring the sexy triple threat of Dakota Johnson, Chris Evans, and Pedro Pascal (Zaddy, as my family says), Materialists tells the story of an NYC matchmaker (Johnson) caught between her broke ex-boyfriend (Evans) and an older-but-new, suave billionaire (Zaddy). The central premise of the film, which I take as a good-faith commentary on modern dating, is that material obsessions incorrectly set our expectations for love: we think we can find the perfect partner if we find someone who perfectly checks all our boxes (height, job, politics, family upbringing, etc). To our protagonist’s clients, love isn’t spontaneous; it’s lab-grown, as perfectly curated as our exercise schedule or social media algorithm. Of course, the movie concludes that love isn’t so simple: it’s messy, irrational, and passionate—all opposites of the cold and calculating power we desperately try to exert over Romance.

Materialists received mixed reviews. It was marketed as a new Rom-Com at a time when the genre had been largely pronounced dead, but was not received by diehard Rom-Com fans as such. That’s because in practice, it was an odd mix of the Rom-Com formula (love triangle, NYC, will-they-won’t-they, hot people, etc) executed by a former playwright who had just written Past Lives: a bittersweet drama filled with more heavy silences than the upbeat, why-can’t-that-be-me shenanigans of Romantic Comedies. In other words, it lacked a lot of the Comedy. So while the genre purists were lighting the film on fire in reviews, the rest of us were still stuck with a movie that was emotionally confusing, underwhelming, and just mid.

Trailer expectations aside, Materialists wasn’t bad because it was boring. It was two hours of close ups on beautiful people, funny (the few times it tried to be), and most of all topical, illustrating what almost every young urbanite in 2025 agrees on: dating sucks. The problem is that, while it was an apt description of symptoms, it had an incorrect diagnosis.

Song’s characters are correct that “love is easy; dating is hard.” And the movie leads us to believe that dating is especially hard because our material anxieties are all-consuming, and that we are consequently preoccupied with all the wrong things. That’s not unfounded in a world where young people are worse off than their parents for the first time in generations. But as tempting as late-stage capitalism makes that theory, there’s something more insidious undergirding this materialism: our decaying social lives.

Derek Thompson has been writing about what he calls the “Anti-Social Century” for a while now (he’s also one of the Abundance guys, if you follow politics). Most recently, he penned a great piece in which he examines recently released data from the American Time Use Survey, and the results for young people today compared to 20 years ago are alarming:

Americans aged 15-to-24 spent 70 percent less time attending or hosting parties.

Face-to-face socializing has plummeted by about 20 percent across the board. It’s 35 percent for unmarried men and people younger than 25.

The amount of time that Americans say they spend helping or caring for people outside their nuclear family has declined by more than a third.

These are just the top lines. More niche and all the more concerning:

Men who watch television now spend 7 hours in front of the TV for every hour they spend hanging out with somebody outside their home.

The typical female pet owner spends more time actively engaged with her pet than she spends in face-to-face contact with friends of her own species.

Last year was the first on record, going back to 1975, that fewer than 50 percent of high school seniors said they’d ever had a drink of alcohol.

None of these facts are actively explored in Materialists. But even still, it doesn’t mean they aren’t lurking in the background. How do I know?

None of the characters have friends.

Dakota Johnson has no friends outside of her coworkers, and she is constantly filling in as a friend for her clients. In one of the opening scenes, she convinces a cold-footed bride to walk down the aisle when the incompetent bridesmaids can’t. Later, when another client is being stalked by her sexual assailant, the client openly admits she has no friends to call except her matchmaker. The same is true at the male vertices of her love triangle: Pedro Pascal lives in a big empty apartment and only ever mentions his brother as a confidante, while Chris Evans lives with roommates he hates. Most of all, no one in the film is seen having fun outside of dating or working—in a movie meant to be a Rom-Com.

This social isolation is pervasive, and it creates an anxiety that undoubtedly affects our romantic lives. Faith Hill writes in The Atlantic that this is leading to the generational loss of a classic rite of passage: fewer people are getting into relationships. For example, in 2023, the Survey Center on American Life found that 56 percent of Gen Z adults said they’d been in a romantic relationship at any point in their teen years, compared with 76 percent of Gen Xers and 78 percent of Baby Boomers. It’s no wonder we are the generation that invented the term “incel”.

She continues that it’s not so simple as “everyone’s single.” The mainstreaming of situationships—emotionally and romantically intimate relationships that aren’t “officially” labeled—is a great example. In a 2024 YouGov poll, half of respondents aged 18 to 34 said they’d been in one. So while kids these days don’t have as many boyfriends/girlfriends/partners, they might still be engaging in emotional intimacy without calling it what their parents called it.

But even if this generational shift is semantic rather than social, the semantic matters. Something within us still fears the vulnerability that comes from openly admitting you are seeing someone or even have feelings for someone. We are terrified of being romantically earnest, lest we commit the ultimate Gen Z sin of being cringe. Without this raw admission, we don’t get the emotional satisfaction we have evolved to crave as fundamentally social creatures. So it might not be that “everyone’s single,” but it sure does feel like everyone’s lonely.

This social anxiety, even if subconscious and collective, is not special. Any anxiety stems from uncertainty and creates a vicious feedback loop of fear. We don’t like what we don’t know, so we avoid it, which brings relief in the short term but reinforces that fear in the long term. Over time, it creates a disconnect between what we do and what we get: we think we’re protecting ourselves through avoidance, yet we do not feel safer. The consequence is a deep sense that we lack control over our own lives.

Lacking control is especially anxiety-inducing in a world where it has never been easier to tailor our exact preferences in all aspects of life. Our phones put every movie and show in the history of the world in our pocket; our social media algorithms learn to feed us increasingly specific content; meal kit services pre-prepare dinners fine-tuned to our diets; Amazon delivers everything from pots and pans to horse-shaped dildos (in two days with Prime!); the DSM-5 now recognizes nearly 160 distinct mental disorders with which to diagnose our personal idiosyncrasies (including a desire for horse-shaped dildos); and, of course, dating apps literally allow us to select the same preferences parodied by Johnson’s bougie clients in Materialists. So it’s only natural that most people expect to select the perfect partner the same way we select the perfect Alexa settings.

We have become conditioned to select people, then meet them; rather than meet people, then select them. It’s a social-emotional defense system that fortifies isolation and avoidance rather than dismantling it.

There is no doubt technology plays a role here. In fact, the information age has formed a nasty love triangle between our social lives, romantic lives, and technology. The first two are a match made in heaven: romance thrives among social abundance, and they play off each other effortlessly. More parties, more connection, more opportunity. But technology is a home wrecker. It seduces us to a warm bed and a cool screen, siphoning energy from our social lives to choke our romance. It’s messy and dark, no more of a classic Rom-Com love triangle than the lurking nihilism of Materialists.

Then again, I hesitate to blame all of this on technology. I don’t think it explains everything, even if it gets close. After all, I’ve written before about Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone and the decay of social institutions, a trend that long pre-dates the smartphone. What’s more, the Zoomers in Faith Hill’s Atlantic article don’t pinpoint technology as the bane of their existence. Instead, many of them simply revere independence:

They didn’t like the idea of only one other person being meant for each of us, or the suggestion that they’d be incomplete without such a reunion[...] they wanted to be whole all by themselves—not dependent on a soulmate.

To be “whole all by yourself” doesn’t have anything to do with your phone—if anything, self-sufficient technologies make that easier. But it does mean Gen Z is wary of needing or wanting social interaction. And technology has become a prerequisite to nearly every social interaction we have, increasing the burden of physical connection by adding yet another step at a time when we just might not care enough.

Consider just how many of our interactions are mediated by screens rather than people. We order DoorDash instead of talking to the guy at the register; we do self check out at the grocery store; we Slack and Teams our coworkers, often while working from home, more than we talk to them; we watch recorded lectures at 9pm instead of showing up to class at 9am; we watch porn instead of having sex; we go on dating apps more than we go on dates. As easy as it is to get what we want, it is equally easy to avoid social interaction while doing it.

Perhaps, then, Materialists is not about the materialism of desiring nice cars or clothes. It’s about our desire to treat people as material objects, finitely available yet infinitely customizable, like our iPhone—so long as they make us “whole all by ourselves”. The result is, ironically, a limited capacity to expose ourselves, openly and vulnerably, to the messy, chaotic, material world around us.

I think there’s a deeper reason Past Lives made me cry. More than just the obvious.

Ultimately, it was about the love that never was. It was about the potential of connection, but not the connection itself. A feeling of longing, of wishing, of wondering what could be despite what is. The entire film was two characters staring into each other’s eyes, imagining some future life together that they won’t experience in this one. And yet, they do it knowing that that’s okay: one is already happily married and the other has a successful career in another country. They were content with longing, or at least they had to be.

I think a lot of people feel that way right now. We are sitting on the subway or wandering the grocery store, and we lock eyes with that pretty stranger across the way. In an instant, a life flashes before our eyes: the meet-cute, the spark, the flirtatious first dates, the vacations together, the fights, the makeups, and all the quiet coexistence in between. Then, like scrolling through a feed, we forget about it and move on.

I don’t think we want to leave behind monogamous relationships and their emotional symbiosis altogether, a relic of our ancestors like arranged marriages or dowries. We long for connection. We just don’t know how to achieve it. Or we feel like it’s not meant for us. In our most stubborn moments, we say some Stockholm syndrome bullshit like “I want to be whole all by myself.” In reality, we’re just too afraid to be vulnerable and try.

Of all my friends, across high school and college and work, I’m not sure any of them are the “serial daters” that my parents’ generation and their pop culture describe. There’s not a lot of trial and error. No trying for a few months, not working out, grieving the loss of connection in your own way, then picking yourself back up and shrugging it off only to try again once you’re ready. In a world of social scarcity, every opportunity feels like the only one you’ll get. That either means you invest everything or nothing at all. Go big or go home. But the latter is much more common (if we ever even left home at all). I have friends who have either been in one (1) relationship for years, or haven’t been in any for the same amount of time. In other words, there are the lucky few who find something beautiful and hold on to it with all their white-knuckling might; and then there are the rest of us, still searching, with fewer social opportunities and fewer emotional skills to seize them.

It’s not our fault. We don’t control whether the grocery store gets rid of cash registers, or whether DoorDash offers a deal we can’t refuse, or if dating apps trigger a chemical response in our brain that is scientifically not unlike heroin. But it doesn’t change the world that young people are navigating—or how that world is changing us. We come up with personal reasons to justify it: I’m working on myself, I’m focusing on my career, I’m just not meeting the right people yet. Whatever it takes to get Mom off your back after this phone call. Meanwhile, we sink deeper into that nice warm blanket, sick from melancholic atrophy and lacking the social strength to get out of bed, just comfortable enough to not get up and go outside even if, deep down, we crave the sunshine more than the screen.

I felt all of this watching Past Lives. Curtains drawn, blanket tucked, nowhere else I needed to be other than my empty studio apartment. My loveseat is built for two—but when I stretch out my legs and roll to one side, facing a giant TV so close to my face that it drowns out my periphery of the physical world around me… man, it feels pretty comfortable for just one.

Speaking of laying on the couch and not socializing, here’s what I’ve been watching and/or reading lately.

To watch

The Terror: A gritty period piece following an 1850 exploratory vessel that, in attempting to discover an Arctic passage to the New World, is lost and never found. It’s a classic survival story of men slowly losing their minds and turning on each other, but we know from the opening scene that none of them make it home. Only 10 episodes, based on a book. Binge-worthy—if gritty is your thing.

Yellowjackets: I’m late, I know. I watched episode one last night. Holy shit why has it taken me so long to watch this. More thoughts to come.

Companion: I thought this was a sci-fi movie. It turned out to be more of a slasher film, and as someone who does not like slasher films (or anything where gore is the point), I loved every second of it. A really fun imagination of robotic AI, with clever storytelling and compelling characters. The best part? It’s less than 100 minutes.

To read

The Dark Forest by Cixin Liu: This is the second installment of the Remembrance of Earth’s Past trilogy, with the first being the more popular Three Body Problem (Netflix adapted it to a show, season 1 is available now). It’s originally Chinese, so you’re reading a translation that definitely feels like a translation at times. It’s big and slow, and stylistically different from most Western novels, but fuck is it good science fiction. There’s a reason this guy has won like every sci fi award there is.

See below for a Substack by Jordan Stacey that was not cited in this essay, but I have been dwelling on lately and is inspiring a lot of my thinking around love, gender, and sociology nowadays:

No, but furreal:

This is so excellent! Totally resonate with what you are saying. "Technology is a home wrecker" is such a good point. I also was disappointed by Materialists - and the fact that none of them have friends... wow. One of the best parts of When Harry Met Sally is the friends!

I have been thinking a lot lately about how the art we consume doesn't only exemplify where we are culturally, but also does inform the way we think and see the world. It has me wondering what kind of movies and shows could help reverse this loneliness issue in Gen Z

Good reminder I need to watch past lives 🙈